16

Aug

The Innovation Leader Your Company Needs Today

Going digital, the focus for many companies today, continues to rightly demand the attention of leadership teams as they evolve to meet new challenges and expectations.

And digital transformation is to a large extent enabled by innovation, from building new products and services more quickly in order to be responsive to customers, to leveraging data for more efficient operations in HR or supply chain, to developing new disruptive businesses.

Thus, innovation matters more than ever. In our experience, companies that get it right are those that first define the problem. That means being clear about their vision and goals for digital, where they are in their development, and what type of innovation will best help them reach those goals.

What type of innovation leaders are companies hiring now?

Top innovation roles come with very different objectives and titles, and from a wide range of candidate pools—business literature is full of articles offering different taxonomies to capture and classify them. Today, there is a clear change of tide in digital disruption, with more established players using their scale, resources, and lessons learned to take the lead in disrupting their industries and setting their eyes on new ones. One of the consequences of this cross-sector convergence is that when it comes to talent, competition is more intense for skill sets that used to see only specialized demand. It also means that the scope of innovation leadership roles can vary even more widely from one company to another, depending on where they are on their innovation and digital maturity journeys.

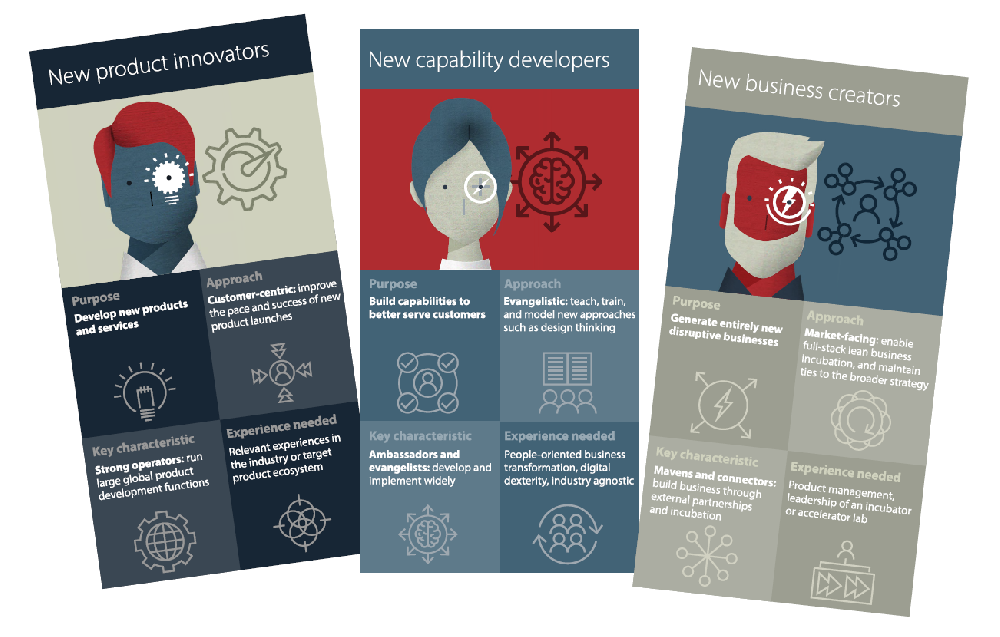

In our experience with a variety of leading companies across industries, innovation leaders today fall into one of three broad categories based on how they deliver value to their companies:

New product innovators

These leaders improve the pace and success of new product launches while exhibiting a keen understanding of customer needs. They have a strong point of view on how customer needs are shifting and what emerging technologies will best meet them. In addition, these leaders are skilled operators capable of efficiently running a large global product development function with an eye on results.

This category of innovation leaders may be considered the most traditional of the current innovation roles, though these leaders work with more urgency in today’s world of accelerating change and shorter product cycles. To be successful, new product innovators must have relevant industry experience or at least have worked in the target product ecosystem, such as consumer Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, or voice control.

Case study: Using product innovation as a source of competitive advantage

A consumer products company was reaching the limits of its new product variations and brand extensions from its decades-old portfolio of beloved brands. In addition, product launches were typically late or delayed and the only major brand launch in years had been unsuccessful.

To salvage its portfolio, the company hired a skilled product development operator with a track record of successful brand launches and experience managing complex design processes at a global scale. Under this new leader’s guidance, the company started using best-in-class agile processes to launch more new products more quickly and with a greater degree of success than ever before.

In less than a year, the company successfully launched a new line of products that redefined a core brand, while cutting overall investment in new product development. The company also saw sales increase and delivered the first quarterly profit in years.

New capability developers

These leaders are teachers who model and evangelize new approaches, such as design thinking, by training and rotating staff through the innovation team to immerse developing leaders in new ways of thinking.

They are strong ambassadors and focus on developing internal capabilities—often entirely separate from the development of new products or services—that will better serve customers. These competencies may include automation of key processes, digitization of functions, or developing new, more responsive supply chains. Further, new capability developers typically have a history of partnering with business units to support change and working closely with peers in IT.

Case study: Improving operations at every level with design thinking

One of the largest US healthcare providers wanted to bend the curve on rising healthcare costs while also improving quality of care as measured by patients, providers, and employees. However, competing with new healthcare service providers that promise high-quality care through technologies such as artificial intelligence, automation, and augmented reality, among many others, was a challenge felt across all functions.

Rather than focus on developing individual innovative technologies, the company set off on a search for a leader who could command a cultural change within the organization.

In launching the search from the top, the company successfully avoided one common trap of innovation efforts—that is, not having executive buy-in. And the company went one step further by not only having the CEO on board but also garnering universal agreement from every member of the executive committee about the importance, and definition, of innovation.

The candidate hired to be the company’s new chief innovation officer brought experience leading design thinking training at organizations with tens of thousands of employees. The purpose of such training is to help every employee, whether checking patients into a clinic or reviewing a claim, think about how he or she can improve customer experiences or create a more efficient process, even in a heavily regulated setting. The team has taken a “learn then build” approach.

Altogether, the changes have led the company to invest in a platform that will enable real-time claims resolution and payment and in hiring more key roles, including a head of clinical innovation and a payment innovation manager.

New business creators

These leaders prefer to look outward. They are mavens and connectors who build businesses by forming partnerships, making direct investments, and incubating new businesses separate from the core enterprise. They are often entrusted with a company’s most strategic, and publicly sensitive, efforts to “disrupt themselves.” In the book Goliath’s Revenge: How Established Companies Turn the Tables on Digital Disruptors (Wiley 2019), authors Scott Snyder and Todd Hewlin note that for large companies seeking to become digital disruptors, business model innovation often drives significantly more value than product and operational innovation.

New business creators, for example, may have developed full-stack development capabilities as part of an incubator or accelerator lab that enables engineering and commercialization of new offerings. However, these leaders still maintain crucial ties to the broader business by staying closely aligned to strategy, following through on opportunities for pilot testing, and incorporating new businesses within the core where appropriate. In fact, maintaining these connections to the core is the primary source of their value to external partners.

Case study: Disrupting the business to unlock more value

Investing in new products that could potentially disrupt the existing business is one of the hardest tasks companies can undertake. Given the potential for internal backlash, these products require radically different development approaches to be successful. Often, leaders selected to spearhead these efforts operate outside of the traditional corporate structure.

One partnership of four companies seeking to access disruptive technologies through venture investing went a step further: instead of each creating their own venture capital investment arm, they created a joint $100 million fund with equal investment from all four members. This structure freed the fund managers to invest across a wider array of technologies, offering higher potential returns both financially and strategically. The fund offers the best of both worlds to its portfolio companies—a greater degree of independence than a typical, single-sponsor corporate venture capital fund and access to four potential growth partners. Other investors provided strong positive initial feedback on the structure, despite the fact that they tend to be wary of bringing inexperienced partners to the table. The structure is expected to be able to deliver strategic value to the four companies by allowing them to access some of the best deals, which are typically “off limits” to corporate venture investors.

How to find the right innovation leader right now

While companies may need a mix of these three distinct skill sets, innovation responsibilities are large and diverse enough that they usually are not met by one person. Instead, companies should select the leader type (or types) that best align with what they are trying to achieve. And while product innovators, for example, generally come from the same industry or ecosystem, companies should be open to candidates from further afield when seeking leaders to be capability developers and new business creators.

Next, leaders who can deliver the degree of transformation most companies require from innovators today are always in short supply. But companies that can tell a compelling story about the opportunities they provide—whether it’s the chance to turn around a product portfolio or build the next great business under a brand that customers know and love—are often the most successful at attracting the right innovators.

Finally, while it is a truism that enterprise-wide initiatives like innovation will not be successful without buy-in from the top, one of the most successful examples we have seen involved buy-in not only from the CEO, but from every single member of the executive team. They were further completely aligned on the goals they were trying to achieve with innovation. Good innovation leaders are necessarily highly attuned to the attitudes of their executive peers, so the fact that the company achieved this degree of dedication and clarity was a key element in allowing the company to attract the right person.

About the author

Christopher A. McCloskey (cmccloskey@heidrick.com) is a principal in Heidrick & Struggles’ San Francisco office and a member of the Global Technology & Services and the Supply Chain & Operations Officers practices.